Introduction to Dialogue

When writing a novel or short story, you will likely want your characters to speak, and thus dialogue is an essential tool you need to strengthen. Indeed, there are instances in stories where characters deliver only a few lines throughout the narrative, yet most include extensive dialogue. By the end of this blog post, you will be better equipped to understand the tips and tricks of conversation.

“If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.” — Elmore Leonard

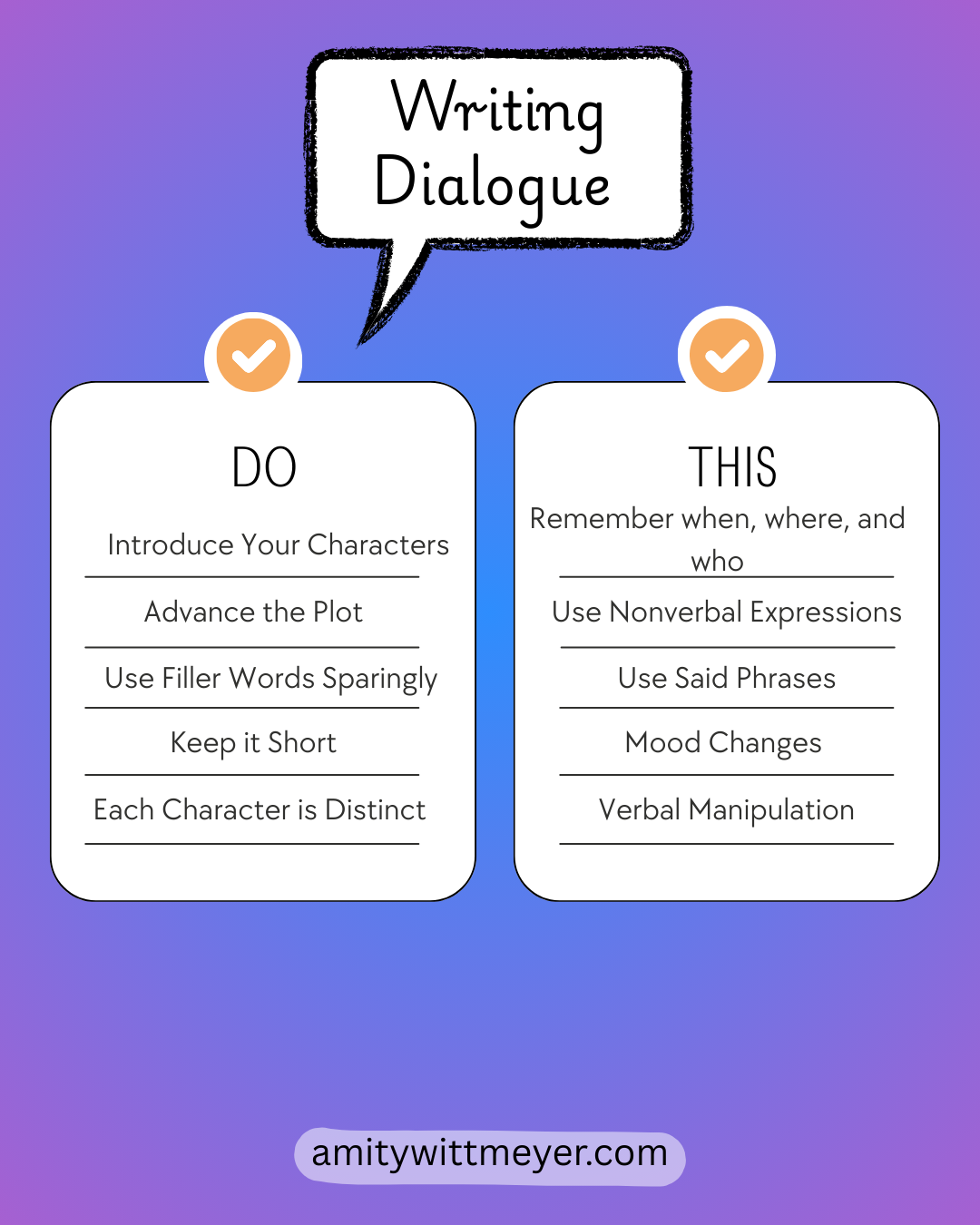

10 Tips for Dialogue Techniques

1. Dialogue Introduces Your Characters and Advances the Plot

Dialogue is a way for your audience to understand who your characters are. They serve a purpose to advance your plot and set the tone. Remember that people can react differently to whom they are speaking and what their objective is to communicate.

2. Use Filler Words Sparingly if Ever

While you want to have accurate dialogue based on real life, be cautious. Remove “filler words” like “uh” or “um”. While this may seem authentic, it solely distracts from your story. Only use filler words in your dialogue if it helps add to the scene or your character.

3. Keep it Short

Don’t write dialogue that expands upon multiple pages. People in real life hardly express themselves in conversation in long monologues without interruption.

To quote the Center for Fiction and their article “Tips for Writing Dialogue,”

“Good dialogue on the page does not resemble actual speech, which is far more unwieldy and convoluted. In general, keep sentences short; people rarely make long speeches or speak in extended sentences in real life (except when lecturing), and it looks even more forced on the page.

4. Each Character Speaks Specifically

To ensure each character sounds distant and separate from one another, focus on their rhythm and vocab. Everyone has set phrases, sound effects, and sayings that are unique to them. Also, remember that a lot of the time, close friends and family start to pick up on each other’s linguistics.

Example:

You are creating a conversation between an older parent and a young child. Without labeling who is who, can you guess which dialogue belongs to each?

“I think my tummy hurts.”

“Oh, your tummy? Well, let’s go lie down for a while until you feel more settled. How does that sound?”

Analysis

Easily, you can tell the first voice is the child, while the second belongs to the adult. Putting aside the context of the dialogue, look at the rhythm and vocabulary used by each character.

The child said a short line using the word “tummy,” which is widley know as a simple term for stomach. The phrase alone helps advance the plot by letting the reader know the child needs something.

The second line has the rhythm of an adult. Firstly, they restate the child’s need to ensure they heard them correctly. Next, they suggest an action to alleviate discomfort.

Remember that each sex tends to find different subjects more important than others, and will discuss the following. Learn more about writing men vs. women in the blog post below.

5. Using Nonverbal Expressions

Now, in real life, people don’t always say what they truly feel. However, their tone can usually give their truth away. So, in writing, how do you express tone? Remember that the literal words your characters are saying don’t necessarily display their feelings. Therefore, utilize body expressions and showing not telling.

What is show-don’t-tell? Find out on blog post below.

6. Use Said Phrases

To be sure, it is common for writers to try to include facial expressions or tone after dialogue. For example, saying something like:

“I am so happy!” She screamed.

Instead of:

“I am so happy!” she said.

While it can seem to be a helpful tool to mix up saying said after each line of dialogue, it can actually do more harm than help. When you use said dominantly, your reader will subconsciously glance over the words, and their main focus will be on your dialogue. When you change it up too much, you disrupt the flow of the reader.

Instead, use descriptions after the phrases “they said.” You can use these expressions from time to time, but the more you do, the less impactful they will be.

Example

Instead of:

“Let’s not be silly,” he screamed loudly.

Try:

“Let’s not be silly!” He said.

More examples:

“I couldn’t believe it,” I said. My hands were still shaking.

“You are mad,” she said, turning away.

“I’ll do it,” they said. They then hurriedly rose to their feet.

“Well, you can try,” he said. He sounded quite sarcastic then and refused to look up from his book.

Analysis

By normalising “they said” statements in your writing, you do not disrupt your reader. Instead, you allow them the chance to interpret what the character is truly expressing and why, without blatantly stating it.

To quote Well Storied and their article “19 Ways to Write Better Dialogue,”

“Dialogue tags are doubtless an important aspect of fictional conversations, but too many tags can also slow the pace of your story — or even draw readers out of your story entirely. Use them with caution and care.”

7. Mood Changes and Verbal Manipulation

When characters are trying to get their way or express a need, remember that they can switch up their tactics during dialogue lines. At first, maybe this character comes across as very friendly. Next, they may try to use manipulation tactics like victimizing themselves, guilt-tripping the other, or bringing up memories to get their way. When those tactics don’t work, don’t be afraid to have your dialogue turn messy, harsh, violent, or even ridiculous.

Example:

A character wants another character to attend Christmas at their house. The second party hates their family and is relentless in avoiding them.

“Hey, what are your plans for Christmas?”

“Oh, the usual. Probably just some takeout and a movie.”

“Aw, that’s so boring. Come home.”

“No, no. I’ll be alright.”

“I know Mom would really be happy to see you. She brings you up every time I visit. I mean, she feels really bad not having you to celebrate the holidays. The whole family just doesn’t quite feel whole, ya know.”

“I think I like my plans better.”

“God, you are so selfish. Can’t you just do this one thing? You’re acting like it’s the end of the world to be loved and with family for an international holiday. It’s one day. Don’t be such a baby.”

“You’re being rude now. You have no idea what you’re talking about. It’s not like you have ever been shamed and constantly nagged for the life you’ve chosen. Our family makes me unhappy.”

“God, listen to yourself. You’re pathetic. This whole god complex you’re displaying is nauseating. Fine, be alone. I guess this is what you get when you try to extend some kindness. You know, I’ve always been there for you, and this is how you treat me? Forget it.”

“Bye-bye.”

Analysis

- Can you notice how, without stating body language or facial expressions, you can visualize the change in the interaction as the dialogue progresses?

- Also, can you clearly tell that these are two separate characters, even though their names were never distinguished?

- Lastly, could you see how short each exchange is and yet each line advances the plot, displays each character’s opinions, personalities, and tactics to defend their own beliefs?

- One thing to note is how each responds to wanting to get their own way. Notice how the first character becomes defensive and starts trying to manipulate the other, who holds their ground. Dialogue is a great way to show how people view their own worth or lack thereof. Difficulties with relationships can stem from attachment styles from childhood and can shift based on personal growth and reflection.

Learn more about attachment styles in the blog post below.

8. Don’t Doddle with Salutations and Exit Phrases

Be nitpicky with what you decide your character says and what is quickly described. In dialogue, you normally don’t continue to say each other’s names back and forth. Even though this may seem helpful to distinguish your characters to your reader, you are actually creating clumsy dialogue.

When it comes to formal introductions and goodbyes, unless each helps move your plot forward, use simple summaries.

9. Be Careful with Accents and Dialects

When you are trying to include an accent or slang terms for your characters, be cautious. A lot of the time, you can simply tell the reader this character has an accent without phonetically spelling their dialogue as they pronounce certain words. Many authors successfully portray dialect through the spelling and punctuation of their characters’ dialogues. Think of Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston, The Color Purple by Alice Walker, or Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë.

Examples:

“Love is lak de sea. It’s uh movin’ thing, but still and all, it takes its shape from de shore it meets, and it’s different with every shore.”

― Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God

However, if capturing language and accents isn’t your strong suit, don’t attempt to do them justice through your spelling. It will be hard to read and usually inaccurate. Tell the reader how this dialogue is supposed to sound instead.

10. Remember Where, When, and Who is Speaking

Make sure your dialogue is true to the location of your story, the timeline, and the class of your characters. If you have included a wealthy character who has had access to formal education, they will speak differently from those who may not have been so lucky. If your story takes place a hundred years ago or a hundred years from now, their slang will be different. Certain words your characters use will probably not be commonly heard in the world right now.

Conclusion

Dialogues are essential in your story to help advance the plot and show your reader who each character is. When you are writing a new story and want to have accurate dialogue between your characters, remember these ten tips and tricks.

Leave a Reply